Carrying the Fire: Memory, Migration, and the Weight of Freedom

It was Saturday December 13th of this past year, 2025, where I found myself in the motherland sitting in a park, embraced by a friend, overlooking families and couples enjoying the festivities of the day. The parade of old cars had ended and faintly you could hear some orchestras but more so the old latin melodies blasting from viejotecas around the city.

The park was draped in gold glittery lights. The palm trees that towered over the park seemed to glow against the darkened sky. It was hard not to fall silent and watch couples kissing, families taking portraits in front of the Christmas tree, the holiday jokers and costumed bystanders waiting for coins tossed to entertain.

The air smelled of cigarettes, marihuana and fried meats but still, in the midst of a city– the air felt fresh and lively. Nothing compared to it, not even my six years in New York City could compare to what Pereira feels like during Christmas.

After a while of sitting on these steps and sharing a small intimate moment with a friend, I realized I didn’t know where I was. He laughed and stared at me incredulously and begged me to guess. I contemplated and looked around again. I blamed it on el alumbrado and the multitudes of people for obscuring and disguising what I should have known to be el Plaza de Bolivar. We laughed and joked and I scoured. He then pointed out that hidden behind the huge Christmas tree and all the bright lights was the famous naked statue.

"Quedó desnudo el hombre, tal un Cristo a caballo. Desnudo el caballo, desnudo el fuego - como en las manos de Prometeo - desnudas las banderas. Nada más, nada menos que un Prometeo: el hombre volando con el fuego sobre la bestia y sobre las montañas en donde los hombres duermen y engendran. Ciegos que buscan la luz. Esclavos que buscan la libertad. Bolívar - Prometeo. Bolívar - tempestad. Bolivar - incendio. Tal es mi estatua. No otra cosa fueron las guerras de independencia ... un anhelo de libertad para conocer, para vivir, para crear."

Roughly translated:

The man was left naked, like a Christ on horseback.

Naked the horse, naked the fire, like in the hands of Prometheus.

Naked the flags.

Nothing more, nothing less than a Prometheus:

the man flying with fire over the beast and over the mountains where men sleep and beget.

Blind men searching for light.

Slaves searching for freedom.

Bolívar, Prometheus.

Bolívar, tempest.

Bolívar, fire.

Such is my statue.

Nothing else were the wars of independence…

a longing for freedom in order to know, to live, to create.

That is what Rodrigo Arenas Betancourt reflected on his statue of Simón Bolívar. And it was poetically realized, this ode to freedom, as I watched families, poor and rich alike, gathered beneath the lights, the park glowing almost heavenly against the dark. They celebrated life and the coming birth of Christ, unaware perhaps that behind the tree, behind the ornaments and the noise, a naked man still flew with fire.

I wondered then what freedom meant in this moment. Not the freedom of independence wars or heroic sacrifice, but the quieter kind: the ability to gather without fear, to kiss in public, to laugh loudly, to linger in the night air without urgency. Bolívar’s fire once promised the right to know, to live, to create. Now it hovered over children chasing each other through cigarette smoke and tinsel, over couples posing for photos they might never print, over vendors counting coins and dreaming small dreams.

The statue did not dominate the plaza; it waited. Like a memory half-buried beneath celebration, it reminded me that freedom is never finished. It is rehearsed nightly in public spaces, tested in who is allowed to rest, to gather, to belong. Watching Pereira glow, I felt both pride and unease. The fire still burns, but it asks to be carried again, not by heroes on horseback, but by ordinary bodies moving through the light, insisting on joy in a world that often denies it.

As I sat there, I became acutely aware of my privilege. The quiet, undeniable privilege of belonging to more than one place, of being able to move between two homes. The thought settled heavily in my chest. The return to the United States loomed like a waking nightmare, inevitable and unsparing. I wondered if it was selfish, as the child of immigrants, to long so deeply for the motherland rather than for the country where I was born.

My parents crossed borders out of necessity, not nostalgia. They fought for safety and dignity in a country that did not want them, and somehow they won. They built a life through endurance and sacrifice. And here I was, their daughter, aching to remain in their land, in my land, held by familiar faces, by language, by customs, by the spirits of ancestors who shaped me long before I knew their names. I asked myself if this longing was a betrayal of their struggle, or its inheritance.

I held my friend a little tighter, as if proximity could delay departure. I tried to absorb everything: the warmth of his body, the hum of the park, the glow of lights against palm leaves. I knew I would soon be leaving without fire in my hands, flying north toward a country that speaks endlessly of freedom while practicing its absence.

Back in New York, the fire would feel distant. I would return to a city braced in fear, where immigration raids ripple through neighborhoods like aftershocks. Where parents disappear on their way to work, where children learn early to memorize phone numbers, where doors are opened cautiously, if at all. The language of liberation here in the States is bureaucratic, sharpened into acronyms and uniforms, rendered faceless. Fear becomes routine. Indifference becomes policy.

I now walk these streets again carrying the memory of Bolívar naked and burning in the dark, and feel the dissonance sharpen. The fire was never meant to be carried alone. It was meant to be shared, to illuminate, to unsettle. And as I boarded the plane back to the United States, I understood that my longing was not selfishness but grief: grief for a world where freedom is unevenly distributed, where belonging is conditional, and where the most vulnerable are asked to prove their humanity over and over again.

I arrived in New York with no fire in my hands, only the memory of it. But memory, I am learning, can still burn.

When I returned to New York, winter had settled in, and with it the familiar quiet panic that moves through immigrant neighborhoods when rumors begin to circulate. A van spotted on the corner. A knock too early in the morning. A workplace raid whispered about in Spanish and passed from phone to phone like a warning flare.

I sought refuge and contemplation in my books of Goya and I landed on a painting that I had the honor of seeing once and sitting with at El Prado in Madrid in February of 2019.

El Prado, Madrid taken in February of 2019

Francisco de Goya painted El tres de mayo de 1808 not as a moment of war, but as a moment of exposure. The men about to be executed are illuminated, stripped of anonymity by a brutal lantern. Their faces register terror, prayer, disbelief. The soldiers, meanwhile, are turned away from us. They are uniformed, mechanical, interchangeable. Goya makes a choice about where humanity lives in the frame and where it does not.

The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid, or “The Executions” Goya y Lucientes, Francisco de. ©Museo Nacional del Prado

That imbalance feels painfully familiar.

In modern immigration raids carried out by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the same visual logic persists. Agents arrive masked, armored, faces hidden behind bureaucracy and law. The people taken are exposed fully. Their names, their tears, their fear circulate publicly, while the machinery that removes them remains faceless and protected. Violence today rarely needs a firing squad; it only needs paperwork and plausible deniability.

Goya’s victims are not shown resisting. They are not armed. They are not guilty in any moral sense. They are simply in the wrong place under the wrong authority. That, too, echoes now. So many targeted in raids are workers, parents, people who have lived quietly and contributed for years. The state reframes their existence as a crime, just as the empire once reframed survival as rebellion.

What haunts me the most in Goya’s painting is not the moment of death but the inevitability of it. The pile of bodies already executed at the edge of the canvas tells us this violence is routine. Rehearsed. Efficient. And that is what makes it modern. Today’s raids function similarly. They are not exceptional events; they are scheduled, funded, normalized. Trauma is administered systematically.

As the child of immigrants, I move through this landscape with an uneasy duality. I carry the privilege of return, of documents, of mobility. I fly freely between countries while others are trapped in the glare of the lantern, praying not to be seen.

I think back to Bolívar flying naked with fire over the mountains, and to Goya’s man in white with his arms raised, illuminated and doomed. Both figures are exposed. Both burn with meaning. One represents the promise of liberation; the other, the cost of power. Between them lies the tension of history repeating itself under new names.

Goya was not painting the past. He was warning the future.

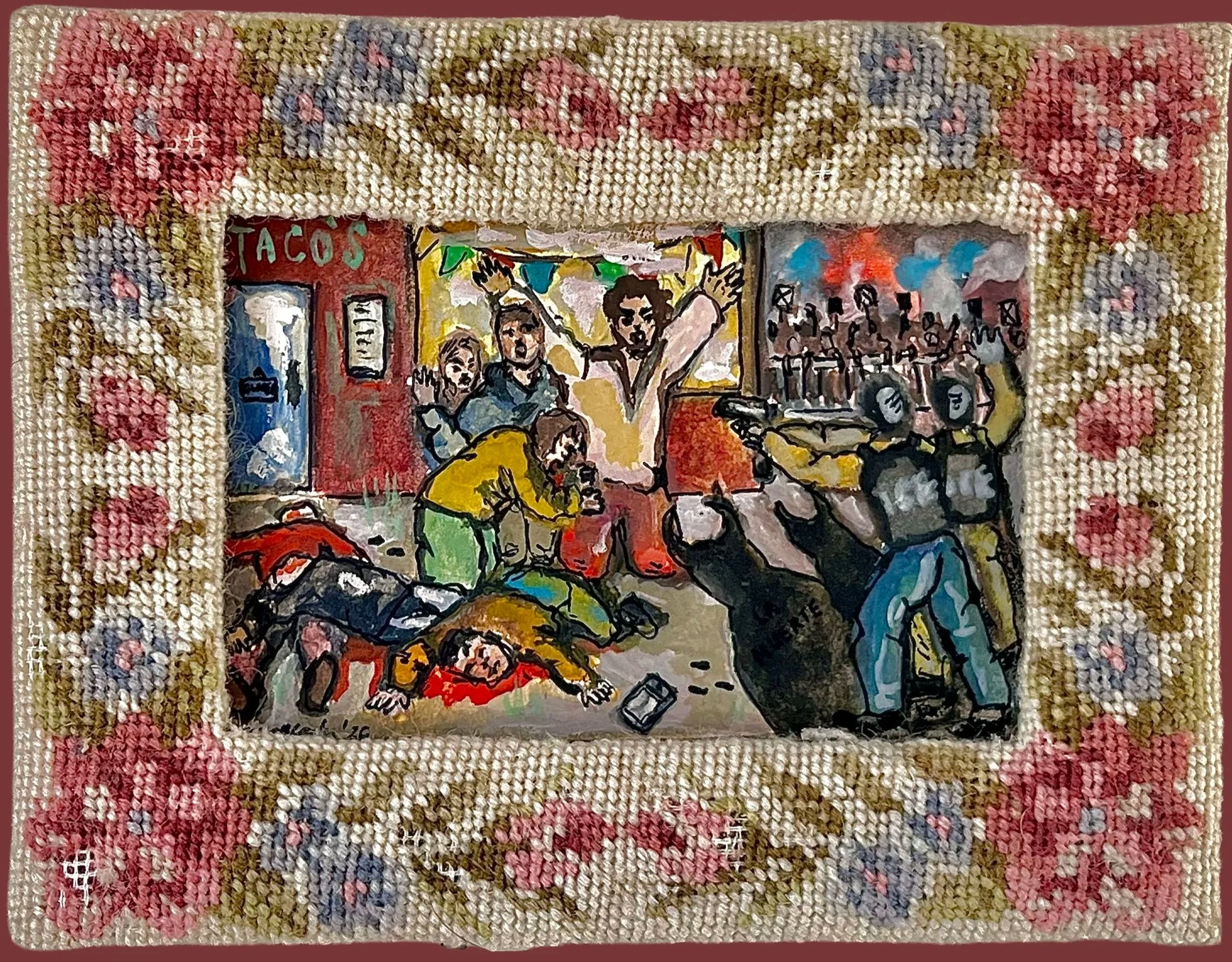

Seguimos en 1808 , 2026 , beginning sketch

I found myself reading James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century, as a guide to a another essay I wrote expanding on the ideas of freedom and passports as a conceptual object consciously designed for control. In the section on migration I found a quote by Walter Benjamin that Clifford included as an opener that really stuck.

“The term ‘origin’ does not mean the process by which the existent came into being, but rather what emerges from the process of becoming and disappearing. Origin is an eddy in the stream of becoming.”

If origin is not the beginning but an eddy in the stream of becoming, then that night in Pereira was not a return to something fixed or pure. It was not a clean reunion with roots buried neatly in soil. It was a vortex of time. Bolívar burning behind the Christmas tree. Goya’s lantern blazing in Madrid. ICE vans idling in Queens. My parents crossing borders decades ago. All of it circling at once.

Origin, then, is not 1810. Not 1808. Not 1990. Not 2025.

Origin is that moment in the park when the statue revealed itself again, naked and waiting. It is the instant when Goya’s executed man lifts his arms in a gesture that mirrors both surrender and crucifixion. It is the uneasy awareness of privilege that pools in my chest as I board a plane north. These are not beginnings. They are formations. Whirlpools where past and present lock eyes.

Freedom itself becomes such an eddy.

In Pereira, it gathers as laughter, cigarette smoke, fried meat, tinsel, the ability to linger. In New York, it fractures under paperwork, uniforms, rumor. It does not disappear. It reshapes. It swirls through fear and endurance, through community text chains and whispered warnings. It reappears in memory, in art, in witness.

The statue waits behind the tree. The lantern burns on the hill. The van idles at dawn.

History does not move in a straight line from liberation to safety. It loops. It drags. It gathers debris. It forms temporary shapes that feel solid until they dissolve again. Bolívar’s fire did not end with independence. In this same breath, Goya’s warning did not end with empire. It resurfaces wherever authority hides its face and calls violence order.

I used to think belonging meant locating an origin point and holding onto it. Now I understand that belonging may be the courage to stand inside the current. To recognize that identity is not a root but a confluence. A meeting of waters carrying grief, pride, privilege, memory, and resistance.

Seguimos en 1808 , 2026 , in progress

Perhaps Bolivars fire was never an object to carry. Perhaps it is the pattern that forms when memory refuses erasure. The heat that gathers when images collide.

Origin is not where I began.

It is where the forces of my life converge and briefly hold their shape.

And in that convergence, I see clearly: memory is not passive. It is kinetic. It moves. It unsettles. It ignites.

The eddy does not stop the river.

But it makes the river visible.

Seguimos en 1808 , 2026 , framed gouache on paper , 5 ×7 in

Get involved:

Find selected information on immigration, rights and ICE in the link below: (click on button)

Source sites for more extended information + you can donate to these organizations directly on their sites: (click on button)

Donations + Information on aid for Cuba due to United States Illegal Blockade: (click on button)